Ancient Greek Homosexuality and Perspectives on Love

I was going to publish this article months ago, right after the Hellenic Republic (Greece) passed the law recognizing homosexual marriage. But I was busy, so it took me a long time to finish writing this. This event had a significant impact. Greece is the first Orthodox Christian majority country to recognize homosexual marriage. Many members of the Greek Orthodox Church voiced their opposition, and Greece’s Balkan brother countries ridiculed them. As we know, Orthodox Christianity opposes homosexual activity, and the Bible explicitly states that sexual activity between two men is sinful. This article will not focus on arguments or show my side. Instead, I aim to explore perspectives beyond what people typically discuss. So, let’s think again. This article will be based on “Sexual Life in Ancient Greece” by Hans Licht and “Symposium” by Plato.

Before discussing homosexuality, let’s talk about marriage. What exactly is marriage? Our current views on marriage and romance mostly date back to the 18th century. In ancient Chinese society, polygamy was common. Both wives and concubines could share their husband’s sexual activity. It wasn’t until 1950, after the Communist Party took over China, that a law was made against polygamy, stating that only monogamy was legal and recognized by the government. In Western society, according to the Old Testament, ancient Israeli people practiced polygamy, with King Solomon having 700 wives. In ancient Greece, marriage between a man and a woman was primarily a social and economic arrangement rather than a romantic union. Humans need to reproduce, making sexual activities between men and women necessary. Marriage was a way to legalize these sexual activities.

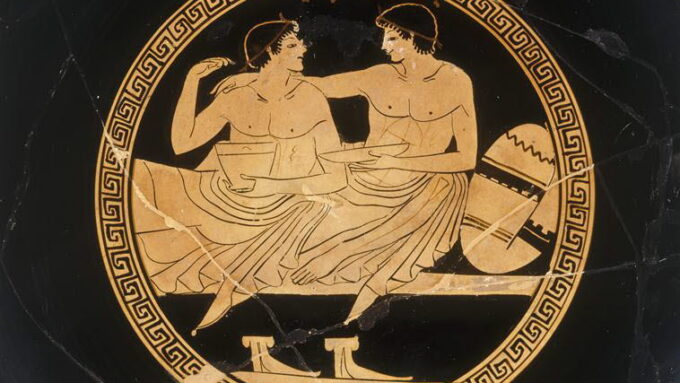

“Male homosexuality” was an accepted and common practice and was seen as the real form of love. It was part of social and cultural life. The ancient Greeks made a clear distinction between the love of a man for a woman and the love between males. The love between males, particularly between an older man and a younger boy, was highly idealized and often associated with mentorship and education.

In ancient Greece, the older man or mature man in a homosexual relationship was called the “erastes,” and the younger man was called the “eromenos.” This mentorship prepared the younger boy for adulthood, instilling values and knowledge that would help him become a successful and respected member of society. The relationship was mutually beneficial, with the eromenos receiving valuable life lessons and the erastes enjoying the companionship and admiration of the younger boy. The erastes would teach everything he knew to the eromenos, who would, in return, offer his youthful body.

In Athens, there were famous couples such as Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who were lovers known as the Tyrannicides for their assassination of Hipparchus, the brother of the tyrant Hippias, for which they were executed.

The famous politician Solon (c. 630 – c. 560 BC) made laws banning slaves from participating in homosexual activities with free-born youths because he believed that such relationships were a privilege reserved for free citizens and should not be degraded by involving slaves.

In Sparta, a society known for its martial prowess, homosexuality was more common and widely accepted. Engaging in a sexual relationship with a mature man was almost a compulsory experience for every Spartan boy. If a young man did not have an older male lover, he might be ridiculed as it was believed that he lacked charisma. This societal expectation is similar to modern ridicule faced by those who delay getting married beyond a certain age. Interestingly, the 300 Spartans, renowned for their stand at the Battle of Thermopylae, included many who were likely involved in such relationships, reflecting the broader acceptance of male homosexuality in Spartan culture. Spartan men grew their hair long upon reaching adulthood, considering it a symbol of masculinity. According to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, Spartan warriors would comb their hair before going into battle, believing that while they might lose their lives, their hairstyles should remain impeccable.

Wait, so does that mean?

In the sparta movie they are all gays?

Homosexuality existed not only between mature men and teenagers but also among adult males and females. For example, the famous gay friends in Greek mythology, Achilles and Patroclus, were an adult same-sex couple. Many ancient Greek literary works depict their love story until death, the most famous being Homer’s epic poem “The Iliad.” Representatives of female homosexuality include the famous ancient Greek poet Sappho. The word “Lesbian” evolved from the island of Lesbos where Sappho lived. Of course, love between adult men and women was less commonly idealized in literature and art.

To understand why homosexual love was so famous and praiseworthy in ancient Greece, we must discuss the philosophers. Here comes Socrates and the “Symposium” (Συμπόσιον). I wrote about the “Symposium” in my last article, “Accepting Death: Socrates and His View of Love.” “Symposium” was written in 385–370 BC by Plato. It describes a meeting between noble people in Athens, including Socrates, Agathon (the first writer to create fictional themes through imaginary characters), Alcibiades, and Aristophanes. These people gathered to celebrate Agathon’s award. The main topic was love and sex. In the symposium, everyone was challenged to deliver a panegyric, a praise of Eros, the god of love and sex in Greek mythology. Thus, praising Eros represents the praise of love and sex. “Symposium” is a short story that can be read in thirty minutes.

The story is based on conversations at this meeting, resembling a drama. I did not introduce the entire story in the last article, but I will finish it here.

The first speaker is Phaedrus. “Love is the great God,” he starts. He believes that the God of Love is the first god born in the chaos of the beginning, existing from the very start of the universe. Love provides the greatest good for people, guiding them to live well and achieve great things. It instills a sense of shame for acting poorly and pride for acting well. It motivates people to act honorably and bravely, especially in the eyes of their beloved. Lovers are inspired to perform heroic deeds and avoid shameful behaviors. No matter how cowardly a person is, inspired by love, he can become a hero, willing to die rather than be shamed in front of his lover, willing to die rather than abandon his lover. If a city or army were made up of lovers and their beloved, they would be unbeatable because they would strive to be honorable and courageous. Lovers are willing to sacrifice their lives for each other, like Alcestis, who died for her husband, and Achilles, who avenged Patroclus despite knowing it would lead to his own death.

The second speaker is Pausanias. “There are two kinds of love,” he said. There are two kinds of love because there are two stories about how Eros’s mother, Aphrodite, the goddess of sexual love and beauty, was born. One is from Uranus (the god of the sky), representing the heavenly Aphrodite. The other is from Zeus and Dione, representing the common Aphrodite. These two Aphrodites represent two different kinds of love. The first, heavenly Aphrodite, is purely male-directed towards boys and is considered noble. It is concerned with the soul rather than the body and aims for lifelong companionship and the moral and intellectual improvement of the beloved. The second love, common Aphrodite, is indiscriminate, directed towards both women and boys, and focuses on physical pleasure rather than emotional or intellectual connection. Pausanias believes that true love exists only between people of the same sex. However, homosexuality does not necessarily mean true love because some homosexuals, like heterosexuals, are just infatuated with each other’s bodies. Noble love is the love of one’s soul. Vulgar love, which only loves one’s body and beauty, is transient and purely physical. He encourages Athens to make laws to restrict people who pursue the love of the body, which he calls “vulgar love.”

The third speaker is Eryximachus. By the way, he is also the one who suggested people give speeches. “Pausanias introduced a crucial consideration in his speech, though in my opinion, he did not develop it sufficiently,” he started. Eryximachus first agreed with Pausanias’s idea. But he argued that love is not confined to human interactions but is a universal principle that operates in all aspects of life, including medicine, music, meteorology, and astronomy. As a physician, he believes that there are two kinds of love, healthy and unhealthy, in the human body, and the doctor’s duty is to separate the two kinds of love and eliminate the unhealthy one to protect the healthy love. Opposites (cold, hot, dry, and wet, etc.) restrain each other, and doctors can use medical skills to create harmony in the body. The healthy love here is the noble love, and the unhealthy is the vulgar love. He draws parallels between Love and music, stating that harmony in music is a form of Love. Just as Love brings harmony to human souls and bodies, it also creates harmony in musical compositions. Noble love brings people a healthier life, and vulgar love makes people develop lustful habits, thereby damaging their health. For example, diseases such as HIV, STD, and syphilis.

The fourth speaker is Aristophanes. “First, you must learn what human nature was in the beginning and what has happened to it since…” he started. As a comedian, he told a story of human beings. Human beings were originally spherical creatures with four arms, four legs, one neck with two faces, and two sets of genitalia. These beings were powerful and complete. There were three types of these original humans: males, which descended from the sun; females, which descended from the earth; and androgynous, which descended from the moon. The original males had two male genitalia, females had two female genitalia, and androgynous had one male and one female genitalia. Due to these organisms’ ambitions and strength, they decided to challenge the gods. As punishment, Zeus split these organisms in half, thus they became normal humans. The original male became two normal males, the original female became two normal females, and the original androgynous became one normal male and one normal female. Since then, people who were split decided to find the other half of their original body. This explains why we have male homosexuals, lesbians, and heterosexuals like me. Aristophanes directly admits that sexuality is determined genetically after birth and is unchangeable.

Finally, he concluded that compared with the previous speeches, his theory is valid for both men and women. The highest happiness of human beings is that everyone can find the other half they have lost. However, if we cannot achieve this, all we can do is find the love that comes closest to this ideal under the existing conditions.

The fifth speaker is Agathon. Agathon begins by asserting that previous speakers have not adequately described the nature of Love itself. He believes it is important to first understand what Love is before discussing its benefits. He claims that Eros is the youngest of the gods and therefore remains perpetually youthful and beautiful. He associates Love with qualities such as delicacy, grace, and attractiveness, emphasizing that Love avoids old age and remains close to youth. Agathon attributes the creation of justice, prudence, courage, and wisdom, the basic virtues of ancient Greece, to the god of Love. Although Agathon’s speech contains no philosophical teachings, Plato still gave this speech an extremely beautiful form. Agathon’s speech also supports Plato’s view of love: that the object of love must be beautiful.

Finally, here comes Socrates. Socrates first admired what Agathon had said, then asked if he could ask Agathon some questions. He asked, “At the time he desires and loves something, does he actually have what he desires and loves at that time, or doesn’t he?” This question exemplifies the famous Socratic method, which puts the other party in the argument into conflict by constantly asking questions and forcing him to admit his ignorance.

Socrates: Does Love desire what it lacks?

Agathon: Yes, indeed.

Socrates: Does Love lack beauty if it desires it?

Agathon: Yes, it does.

Socrates: Is Love something beautiful if it lacks beauty?

Agathon: No, it is not.

Socrates: Does Love desire wisdom if it lacks it?

Agathon: Yes, it does.

Socrates: Is Love something wise if it desires wisdom?

Agathon: No, it is not.

Socrates: So, Love is neither wise nor beautiful?

Agathon: That seems to follow.

Socrates: If Love is neither beautiful nor wise, then what is it?

Agathon: I am not sure; you tell me.

Thus, in this way, Socrates undermined Agathon’s idea. After leading Agathon to the realization that Eros (Love) cannot be inherently beautiful or wise if it desires these qualities, Socrates transitions to recounting the teachings of Diotima, a wise woman from Mantineia.

Here we have the speech of Diotima. She begins by explaining that Love is neither entirely beautiful nor entirely good yet exists in a state between mortal and divine. She characterizes Love as a spirit (daimon) that mediates between humans and gods, conveying prayers and sacrifices from humans to gods and bringing divine commands and gifts to humans. Love is not a god but a great spirit born from Poverty (Penia) and Resourcefulness (Poros), explaining why Love is always in a state of need and pursuit, constantly seeking beauty and goodness. Because he received ignorance from his mother and wisdom from his father, he is in between wisdom and ignorance. He admits his ignorance and thus works harder.

Since wisdom is the most gorgeous thing, he is always in pursuit of it. He is a lover of wisdom, a philosopher, from the beginning. The purpose of Love is to give birth in beauty, both physically and spiritually. This desire to procreate in beauty is driven by a longing for immortality. Humans are pregnant in body and soul, and through Love, they seek to create and leave behind something that transcends their mortality, whether it be children, art, or virtuous deeds. Some people reproduce only physically and have children. Others are pregnant in body and soul at the same time, and they are not pregnant with children but with wisdom, virtue, and all the skills of governing a country. Beauty guides these people, but it no longer points to physical beauty; instead, it points to knowledge that can enrich and multiply the soul. This is what I mentioned in the last article about Socrates’ view on death because the soul is immortal.

This is the Ladder of Love, which I have mentioned before.

- Love of a Single Beautiful Body:

- The initial stage involves physical attraction to one person’s body. This is the most basic and immediate form of love.

- Love of All Beautiful Bodies:

- Recognizing that beauty in one body is the same as in any other, the lover begins to appreciate beauty in all bodies. This broadens the lover’s perspective beyond the particular to the general.

- Love of Beautiful Souls:

- Moving beyond physical attraction, the lover starts to value the beauty of the soul. This includes moral and intellectual qualities, leading to deeper and more meaningful connections.

- Love of Beautiful Laws and Institutions:

- The lover appreciates the beauty found in good practices, laws, and institutions that shape society. This stage involves an appreciation of the harmony and order in social structures.

- Love of Knowledge:

- The lover seeks beauty in knowledge and intellectual pursuits. This involves a desire for wisdom and a deeper understanding of the world.

- Love of the Form of Beauty Itself:

- The final stage is the love of Beauty in its purest, most abstract form. This is the ultimate goal, where the lover contemplates Beauty itself, which is eternal and unchanging. This stage transcends all physical and specific forms of beauty, leading to a profound and philosophical understanding of true beauty.

Love is a powerful motivating force that drives individuals to seek higher truths and greater goods. Love is not merely about physical desire but about the aspiration for immortality and the pursuit of true beauty and virtue. Love is about the pursuit of what one lacks and the drive towards greater understanding and connection with the divine.

Diotima: “Do you think, Socrates, that Love is the love of something or of nothing?”

Socrates: “Of something.”

Diotima: “Does Love desire that which it loves?”

Socrates: “Yes.”

Diotima: “And does Love possess what it desires and loves, or not?”

Socrates: “Not.”

Diotima: “Then Love desires what it lacks and does not possess?”

When someone loves something, they desire what they lack. If we lack knowledge, we desire it. We love the things we have never owned. We all love beautiful things because we naturally desire them. This beauty can come from knowledge, wisdom, or physical shape and structure. But who originally told us what beautiful things are? How do we know something is beautiful or not?

This understanding of beauty is innate. Diotima explains that this perception of beauty begins with the love of a single beautiful body and evolves into an appreciation for all beautiful bodies. As one ascends the Ladder of Love, this perception deepens and broadens. The lover moves from physical beauty to the beauty of the soul, then to the beauty of laws and institutions, and eventually to the beauty of knowledge. Ultimately, it leads to the love of the Form of Beauty itself, which is eternal and unchanging.

The stages of the Ladder of Love guide the lover from the most immediate physical attractions to a profound understanding and appreciation of beauty in its purest form. As one progresses, the love becomes less about individual desire and more about the pursuit of higher truths and the cultivation of the soul. True beauty transcends physical appearances and lies in the harmony, order, and excellence of all things. This ultimate realization of beauty and the divine inspires a love that is not just about possession but about the continuous pursuit of truth, goodness, and the perfection of the soul.

Just when Socrates finished speaking, Alcibiades joined the party uninvited. He was drunk and wore a wreath of ivy and violets on his head with many streamers tied around it. After joining the party, Alcibiades delivered a eulogy. However, this eulogy did not praise the God of Love but rather Socrates. Alcibiades was a famous Athenian politician and a famously handsome man. Despite his own beauty, he fell in love with the “ugly” Socrates because Socrates’ wisdom and bravery deeply moved him. In an attempt to become Socrates’ lover, Alcibiades once took off his clothes and got into Socrates’ bed on a cold night. He hugged him and lay there all night, hoping something would happen between them. Unexpectedly, Socrates remained calm and unaffected. The entire night passed without anything happening. On one hand, Alcibiades felt a little hurt in his pride, feeling ashamed and annoyed. On the other hand, he greatly admired Socrates’ rationality and self-control, which deepened his love for him.

Alcibiades tried to seduce Socrates with his beauty, but Socrates remained unmoved. Let’s look at Socrates’ response to Alcibiades:

“Dear Alcibiades, if you are right in what you say about me, you are already more accomplished than you think. If I really have the power to make you a better man, then you can see in me a beauty that is truly beyond description and makes your own remarkable good looks pale in comparison. But then, is this a fair exchange that you propose? You seem to want more than your proper share: you offer me the mere appearance of beauty, and in return, you want the thing itself—’gold in exchange for bronze.’”

This statement aligns with Plato’s Socratic understanding of beauty: Beauty is graded. Rational and orderly beauty is much higher than physical beauty. What Alcibiades wanted from Socrates was the beauty of knowledge and reason, that is, wisdom. He believed that Socrates, like others, would be captivated by his physical beauty and would exchange his status as an imparter of knowledge for the enjoyment of Alcibiades’ beautiful body. However, Socrates had already seen through all this and knew that the beauty of true wisdom transcends everything. Compared to this beauty, the beauty of an individual’s body is like the difference between brass and gold. At the same time, in Plato’s view, reason and desire are two competing aspects of human nature. Only when desire is controlled by reason can a person’s “justice” be realized, making them truly beautiful and good. I heard a story once about a young lady who exchanged her body with a college staff member to secure admission to a prestigious college. Oh, it was such a great college. WAS. This act used a dirty and sinful exchange to insult the divinity of knowledge. Such an exchange is the greatest insult to the true essence of knowledge.

What we think of as wisdom is often just the acquisition of knowledge, just like in the school you listen to your teacher, so many people consider themselves lovers of wisdom. For instence like Agathon, who thought that as long as he sat next to Socrates, he could obtain the wisdom Socrates possessed; and like Alcibiades, who thought he could easily exchange his physical beauty for Socrates’ wisdom. However, the wisdom that can truly be realized in people is actually the practice of an ideal life: only by experiencing it personally can wisdom be truly internalized. When Socrates accepted his death, we known that he actually internalized the wisdom.

A person who, like Socrates, can practice the pursuit of wisdom as their way of life, in the words of Alcibiades, “as a whole, he is unique; he is like no one else in the past and no one in the present—this is by far the most amazing thing about him.” Even today, we can still repeat these words because it is incredibly difficult for a person to resist their own inner desires and the ubiquitous temptations from the outside world and always maintain an innocent heart. For a human nature filled with sin, how difficult it is to maintain the last gift from God—reason, which is true beauty.

That was a lot of words, but they explain one key point. The ancient Greek “homosexual” love is totally different from modern homosexuality. The current one is based on “sexual desire.” Frankly, it is based on the premise of being able to have sexual relations. What the ancient Greeks praised was inspired by the “desire for beauty,” love for beauty and wisdom, and was predicated on possessing virtue.

Fun fact: When I talked with my Balkan friends, they always made fun of Greek people being “gay.” They used examples such as what we just talked about. However, ancient Greek society valued male masculinity, and more feminine men were looked down upon. The Greeks admired traits such as physical strength, bravery, and rationality, which were considered essential qualities of a virtuous man.

From another perspective, we can question whether the ideology of Ancient Greece, including the concept of Platonic love, is truly realistic. Why can’t sisterhood love be like brotherhood (homosexual) love? Where did women fit into this societal framework?

Modern discrimination and opposition to homosexuals largely stem from traditional cultural influences brought by religion, particularly Christianity. This influence extended to Islam, which emerged later. Today, homosexuals face discrimination and even prison sentences in many countries.

Regardless of how we view these issues, it’s important to consider a different perspective. Societal progress must involve challenging and breaking away from original ways of thinking. We tend to believe that the current supremacy of heterosexuality is correct. But can we think about love between people as something beyond reproduction? Does this mean eunuchs cannot experience love? Or consider a more liberal viewpoint where you fully accept these ideas. Is promiscuity driven by sexual desire or wearing revealing clothes in public aligned with human morality?